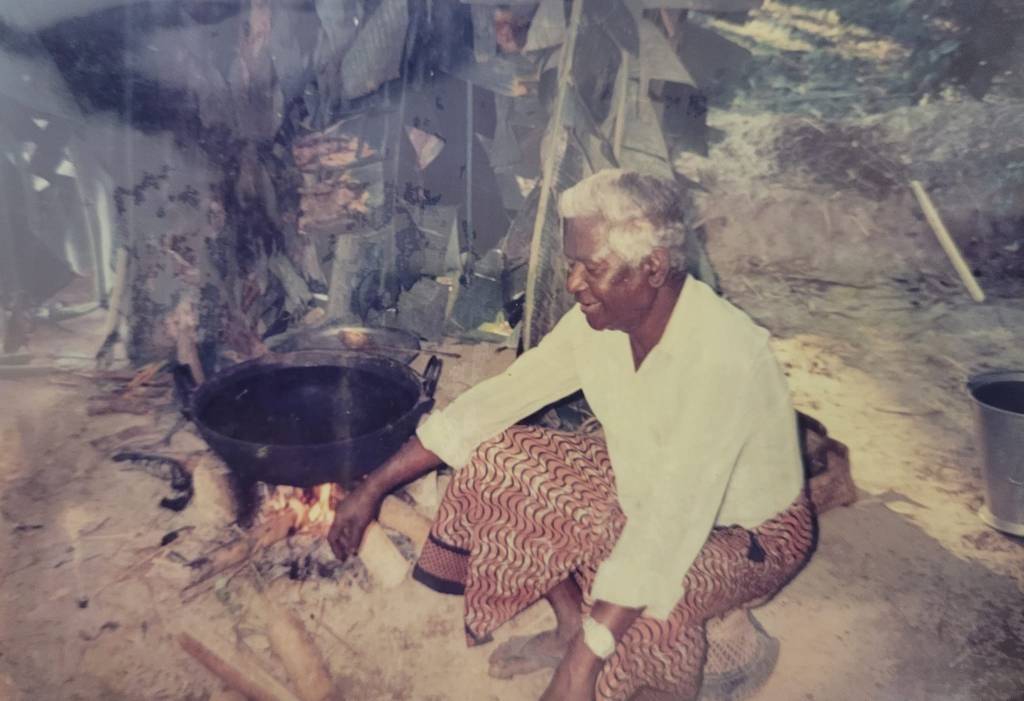

Late Reverend Father Stanislaus Kerketta, sdb (Left; My paternal granduncle),

Late Louis Kerketta (Right; My paternal grandfather)

Trigger warning: death, stroke

I only have faint memories of my paternal grandfather. He passed away when I was a little boy. I remember sitting down together in an evening around a bonfire. Although I do not have more memories of my grandpa (Nana, as I would call him; instead of Dadaji, the accurate Hindi term), I came to know a lot about him through my dad, uncles and aunts. My ‘nana’ was a Hindi teacher at a school, not far away from their house. Apparently he was quite popular as he was respected and loved as a teacher. When I studied the Hindi language in school, I would often refer to a Hindi dictionary that he left behind. It was quite useful and helped me a great deal.

My nana apparently was a kind and loving person. He was quite social. Although he had been a Sarna dharma (Nature worship religion) priest, he was a practicing and faithful Roman Catholic after wilful conversion. My grandma, and relatives after them continue to be practicing faithful. Nana’s untimely death was a bit of a mystery. He had gone to the loo post midnight and was found passed away later with his watch stopped at 2:30 am. My dad preserved the watch in my nana’s memory.

There’s this funny thing my dad told me as a child, to console me whenever there was a thunderstorm and I would get a bit scared, “Tumar nana’e football khelise,” which translated from Assamese into “Your grandfather is playing football.” That would work like a charm in calming me down.

My paternal granduncle, whom I called ‘Father nana’ lived a ‘full’ life. I called him so because he was a Catholic priest. Father nana, or just nana, was a simple, yet hard-working person. He was quite dedicated to his priestly life and also loved my sister and me dearly. He filled any void my sister and I might have otherwise had after the loss of our grandfather. He would get chocolates for us. I remember asking him for a Five-rupee tasty digestive treat once, while going on an evening stroll together. Although he was a Salesian priest and swore an oath of poverty, he did not hesitate to buy one for me. It was only much later that I came to know of the Salesian oaths made at the time of a Catholic priest’s ordination. Nana would be keen on overseeing the vegetation that grew on the Salesian establishments he was posted in, look after the seminarian boys, go to many rural areas to celebrate Mass among other things.

I remember the time when he was posted in Tinsukia. My sister and I would go visit him during summer vacations. He would crack many jokes. Nana had false teeth that he would remove and show us, which amused us a lot. He would let us type letters or simply write on his mechanical typewriter now and then. I would also read a few publications of the Salesians of Don Bosco during the vacations.

Father Nana’s immediate family lived in Jamuguri. Towards the end of his service, he was at Don Bosco Salesian house, Dibrugarh. He would visit us from time to time. We would go visit him too. He was healthy for the greater part of his life. Having a stroke during the last days of his life might have been upsetting as he was otherwise quite an active person, despite being a diabetic. The priests and brothers at the Salesian house took care of him. We also went to visit him; sometimes just mom and dad, sometimes me as well. I could see it in his eyes that he felt helpless. He found it difficult to speak because he was partially paralysed after the stroke. But I could also tell that he was satisfied that we had gone to visit him. He wanted to visit his family in Jamuguri, but the place was far away. He was not in a condition to travel and the Covid-19 pandemic still posed a threat. Later, nana contracted coronavirus and laid to rest in May 2021.

The love and life of both my grandfather and granduncle was something that many hold closely, both family and others, whose lives they touched. Thank you, dear nana’s.